Reflecting on the Berry Bequest (1889), by Tom Jones and Emma Sutton

At his death in 1889, David Berry left £100,000 to the University of St Andrews. At the time, it was by far the largest donation the University had ever received, and it helped the University out of very significant financial difficulties. But where did the money come from, and why was it left to St Andrews?

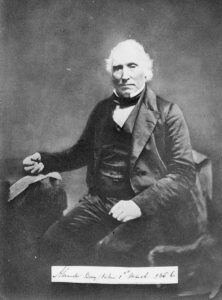

Fife-born David Berry (1795-1889) was Australia’s first millionaire. He ran a plantation in New South Wales that his elder brother Alexander Berry (1781-1873) had established in 1822, having been granted land by the Governor of the State, Lachlan Macquarie, in return for maintaining convicts. Alexander chose to occupy land just north of the mouth of the Shoalhaven River. His convict workforce changed the course of the river to make it easier to navigate. He recruited Aboriginal men, named as Yager and Wagin in his Reminiscences, as guides and intermediaries. They may well have introduced him to a landscape that Aboriginal communities had been managing for generations, making it particularly attractive to exploitation by colonisers. The Berrys engaged in mixed agriculture, including dairy and tobacco, and forestry of cedar. In addition to convict labour, Aboriginal people worked on the estate, primarily for food and clothing rather than wages.

From 1836, David Berry took on the management of the estate as Alexander spent more time in Sydney. David’s practice of paying Aboriginal workers in food was described as considerate in obituaries in the Australian press. Nonetheless, the disrespectful and exploitative aspects of the Berrys’ behaviour reflect common European values of the time and the estate was not always peaceful. Alexander Berry used handcuffs, guns and bayonets to intimidate the Aboriginal population and instructed his business partner Edward Wollstonecraft not to be ‘humbugged’ by Aboriginal people. Moreover, Alexander Berry was engaged in the practice of exhuming the remains of Aboriginal people and sending them to Britain as specimens, in one case specifically as an act of retribution for resistance to colonisation.

Aboriginal Elders and bearers of traditional knowledge state that the Berrys’ attempt to restrict the rights of Aboriginal people to travel across and use the land the Berrys occupied was always contested, and Indigenous leaders who resisted the colonisation are celebrated. Now, this area is the subject of a Native Title Claim, recognising the continued existence of Aboriginal communities on the land from the period before colonisation, acknowledging their connection to the area possessed under traditional law and custom.

In his memoirs, Alexander Berry said he wasn’t afraid of Aboriginal Australian people (to whom he referred as ‘savages’) because of his encounters with Indigenous peoples earlier in his career. Before living in New South Wales, he had been a merchant, trading and travelling extensively, from South America to Aotearoa/New Zealand. In 1819, he wrote an article on his experiences retrieving surviving crew and papers from a ship, the Boyd, that had been taken by Māori at Whangaroa. In his account of this event, he writes about his methods for exerting power and authority over Indigenous peoples.

Alexander Berry’s first profession had been as a ship’s doctor. His medical studies were undertaken at Edinburgh University, but he had begun his university life in St Andrews, following the standard curriculum and borrowing books, including the Voyages of James Cook, from the University Library. Like many contemporaries educated in Scottish schools and universities, Alexander Berry thought about the Indigenous people he met later in his life in relation to his knowledge of the earlier periods of European history: he compared the people of Fiji to the Greeks of Homer’s time in their system of navigation and their treatment of the bodies of the dead, for example. As scholars have come to recognise, the ‘natural history of humankind’ that was being taught at Scotland’s universities at the time Berry attended them had varied outcomes. It could lead to open discussion of the differences between cultural practices in different parts of the world, or it could lead to racist conceptions of the hierarchy and potential for cultural progression of different ethnic groups. Berry’s later attitudes were likely informed by his education here in St Andrews.

In 1884, several years after Alexander Berry’s death, representatives of the University wrote to David Berry’s lawyer, asking him to forward a letter to David Berry. In that letter, the Principal, John Tulloch, reminded David that his brother, Alexander, had intended to leave a large sum of money to the University, but had died with his will unsigned. Tulloch pointed out the hard times the University had experienced. James Norton, the lawyer, and possibly John Hay, the inheritor of the rest of David Berry’s estate, apparently persuaded David Berry to include a bequest to the University in his will. The University suggested it would offer Norton an honorary doctorate of letters if he were successful in his mission (which he received in 1890), and told David Berry it would associate the name of his brother with the University if it received the bequest.

Where, then, does the Berry bequest come from? The money was given by David, recognising the intention of his brother who had attended the University. But doesn’t the wealth that Alexander was able to leave at his death come as much from the land that the Aboriginal people of the South Coast region of New South Wales had lived on and with and stewarded for many generations? Alexander Berry has been said to have been constantly at the brink of ruin until he colonised land in the Illawarra region. Surely the Berrys benefited from the long-term Aboriginal stewardship of the land as much as from their own endeavour. How should we acknowledge benefits that derive from Aboriginal stewardship, and also partly from deforestation and from convict labour?

The Berry Bequest arrived in instalments through the 1890s and early 1900s. It was used for a wide range of purposes within the University, but the name is most widely known for the Berry Chair of English Literature, first occupied by Alexander Lawson in 1897. This is why the School of English has been investigating the history of the Berry family.

The School of English has begun a process to acknowledge publicly the complex history of the Berry legacy. The School acknowledges that the material and intellectual benefits we have derived from the bequest are founded on the knowledge, practices and natural resources of the South Coast People, other Indigenous people of Oceania, and convict labourers. We are considering how to acknowledge and use privileges that came in part from the colonisation of land and claims to its exclusive use that were not recognised by the local Aboriginal communities. The University has long-standing relationships with Indigenous scholars, students and communities in Australia and Oceania. We are grateful for the guidance of Indigenous scholars in reconsiderations of Berry’s legacy and in engaging with those communities who historically and presently are affected by the Berrys’ appropriation of land. We are developing resources and activities, including a prize for Indigenous poetry, to support Indigenous scholarship and creative work. Further details will be announced in due course.

—

Tom Jones and Emma Sutton are both professors in the School of English

—

Sources:

M. Perry, ‘Berry, Alexander (1781–1873)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University

M.D. Stephen, ‘Berry, David (1795–1889)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University,

Bruce Buchan and Annemarie McLaren, ‘Edinburgh’s Enlightenment Abroad: Navigating Humanity as a Physician, Merchant, Natural Historian and Settler-Colonist’, Intellectual History Review, 31:4 (2021), 627-49

Michael K. Organ, Illawarra and South Coast Aborigines 1770-1900, University of Wollongong Research Online [includes transcriptions of selected Berry correspondence]